Jump to winners | Jump to methodology

Common with many other sectors, safety has seen strides in inclusion, but much work remains to be done.

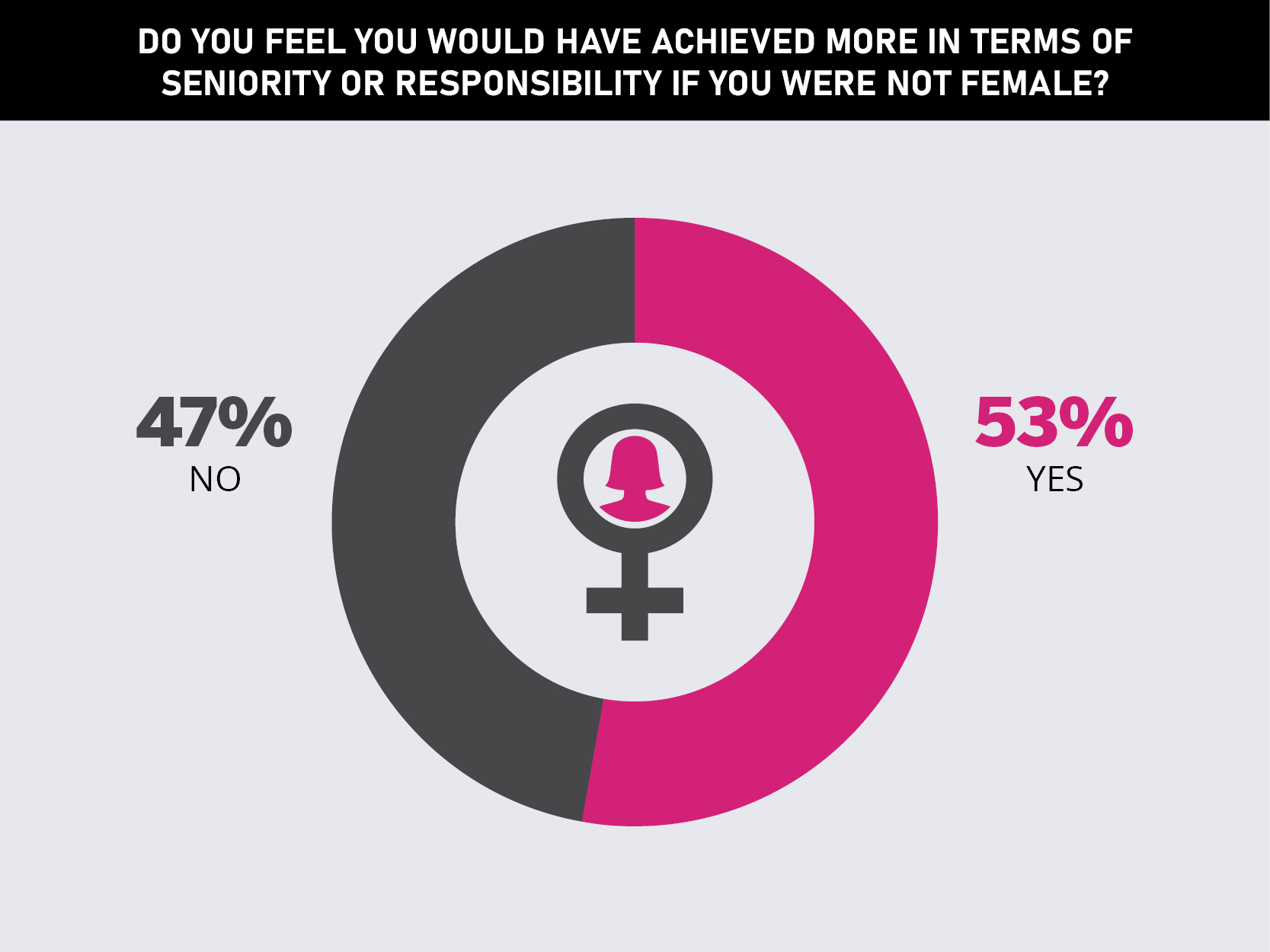

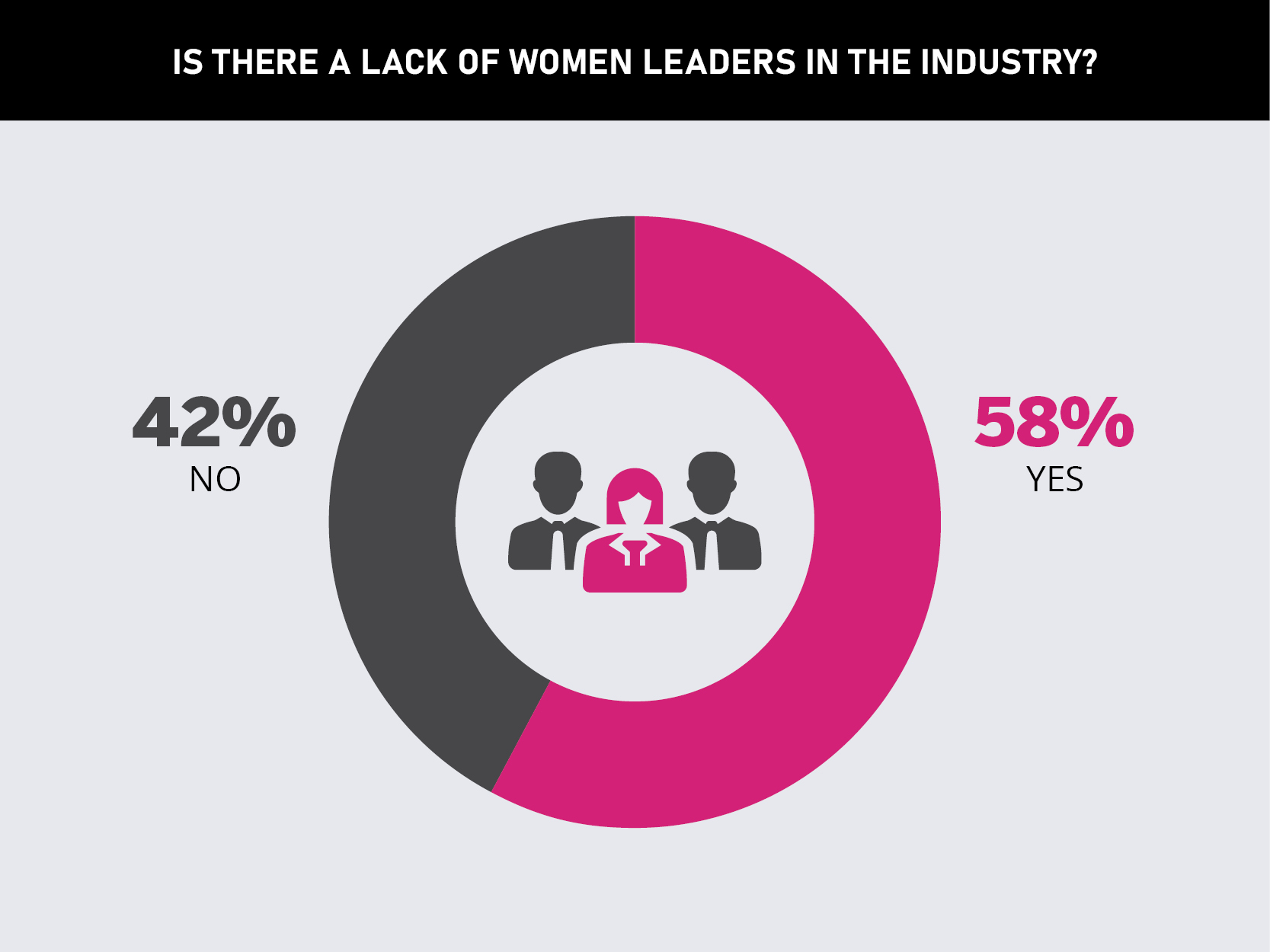

Canadian Occupational Safety’s 2025 data shows that a majority of respondents feel they would have achieved more professionally if they weren’t female and also stated there is a lack of women industry leaders.

Insights shared with COS from female industry respondents included the following:

“Despite progress, women often face skepticism about their expertise and leadership abilities. Balancing professional responsibilities with personal commitments can also be demanding. However, these challenges can be mitigated through strong support networks, mentorship, and advocating for diversity and inclusion”

“Misogyny, harassment, and gender stereotypes can all run rampant if not adequately addressed or if the company’s culture does not place value on tearing down these harmful ways of thinking”

“The most difficult thing about being a woman in the OHS industry is the false belief that we can’t do, or don’t know, as much as men. Women are frequently overlooked for management positions in the OHS industry, regardless of credentials, experience, and performance”

“We are often pitted against each other or seen as too young or too mellow because we do not show our assertiveness the same way as men. We can be labelled as confrontational when we are debating an issue”

Diana Anderson, board chair of the Saskatchewan Safety Council and OHS consultant for the City of Saskatoon, echoes these points.

“Being seen as competent or knowledgeable enough can still be prevalent in some industries, as some are still an old boys’ club,” she says. “There are some women who are breaking into those areas and showing how successful women can be in those areas, but it can be tiring.”

Reflecting on her personal journey in the safety industry, Anderson recalls a vivid memory from her early days in mining.

She says, “In my first mining job, the men’s locker room was by the door the buses dropped us all off at, but the women’s locker room was a 10-minute hike through the shop and up creaky, poorly lit stairs. Women were obviously an afterthought and were treated differently.”

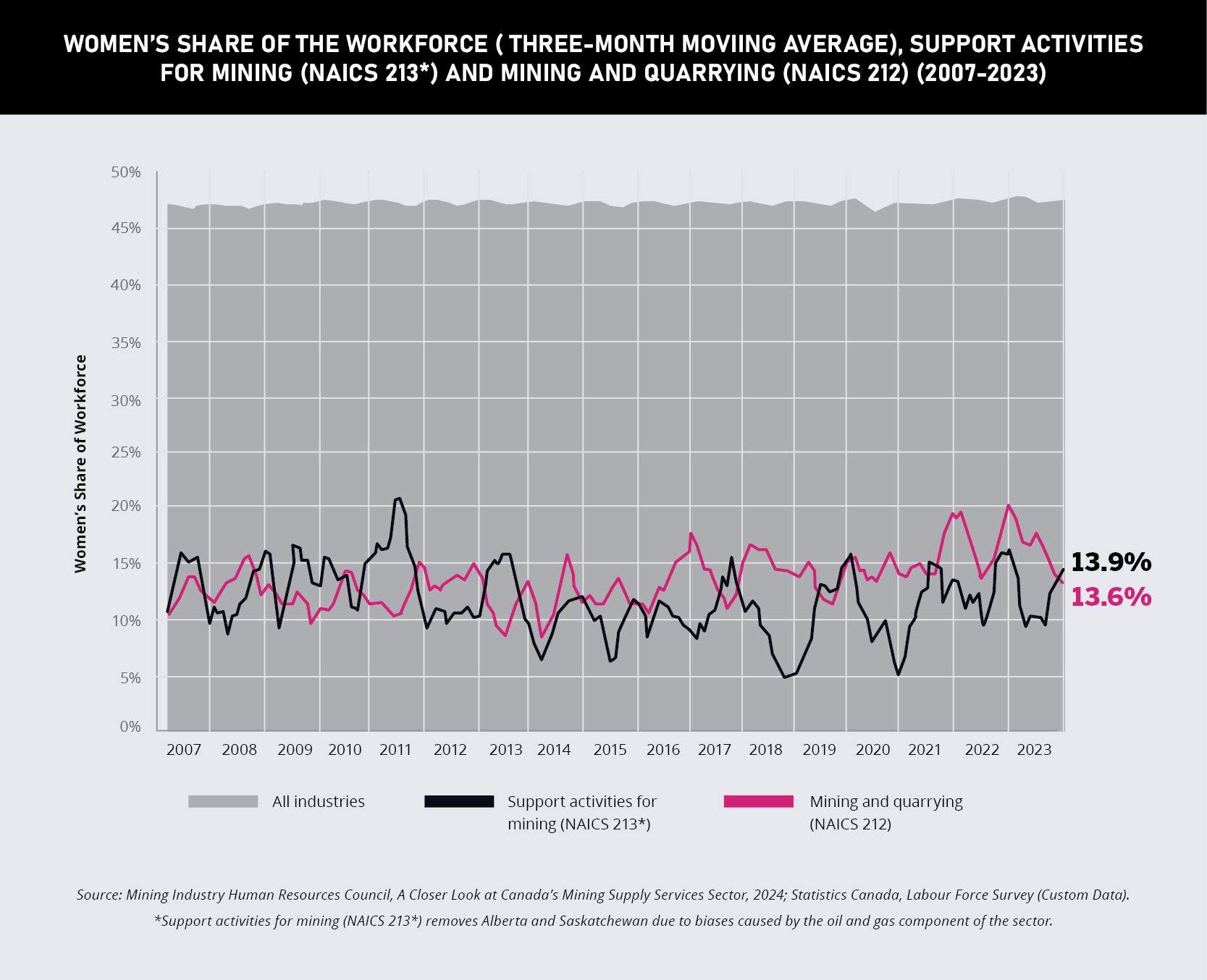

The issue of women not being represented in safety is highlighted in the mining industry, which has significant safety demands.

The independent non-profit Mining Industry Human Resources Council (MiHR) states that “people from diverse backgrounds represent a relatively untapped pool of talent for the mining industry. In 2023, only 15 percent of the mining workforce were women.”

The issue is further highlighted by well-publicized issues with women finding correct-fitting and comfortable PPE to wear, with a significant amount reporting what they have to wear is inadequate.

With all these challenges in mind, respondents to COS’ nomination process highlighted what defines a top female safety leader in 2025:

“The combination of knowledge, integrity, assertiveness, and empathy”

“A true leader takes charge in her field and inspires those around her to reach their full potential and understands and values diversity while staying true to herself and her beliefs”

“Is honest about her strengths and shortcomings. She is constantly learning, either formally or informally, but continues her quest for knowledge and understanding so she can better help those around her”

“Speaking up on emerging issues and seeking to collaborate in finding effective resolutions”

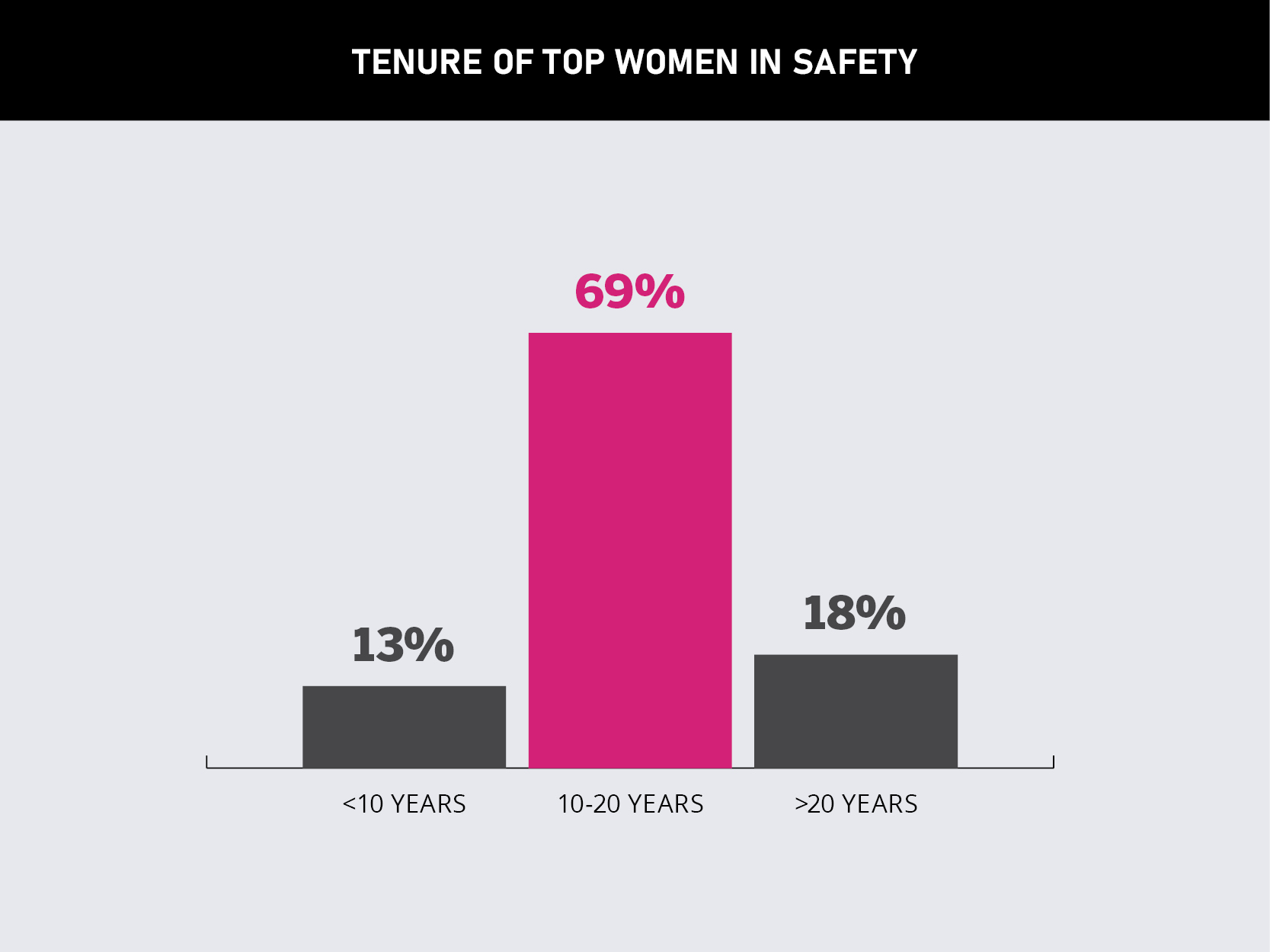

The Top Women of 2025 were recognized for dealing with institutional barriers and their standout professional achievements over the past 12 months, plus innovations and contributions to the OHS industry.

“In terms of earning respect, I always found it amusing when men, who didn’t think that a woman could be a safety person in a male-dominated environment, realized that you are as good or better than the previous man who did the job, and they begrudgingly start to respect you,” Anderson says. “It takes a lot of energy to make that happen sometimes, and it can’t happen without management support, better hiring practices, and persistent, intelligent women.”

Malaryk leads a team of six safety professionals, responsible for the development and execution of the project safety plan, work procedures, initiatives and incentive programs, orientation and training, compliance and reporting, audits, KPIs, incident response, and care.

The current role is the $1.4 billion Union Station Enhancement Project in Toronto for Metrolinx, which will peak with 450–500 people on site.

“We make so many decisions in a day, and we just want to influence the person to make the safe one,” she says. “We want to make sure that we’re not overbearing and not coming in and mandating; we want to be looked at as resourceful and helpful.”

Malaryk’s passion for safety stems from growing up in the trades-focused town of Estevan, SK, crossing paths with many individuals that had experienced life-changing work injuries.

Promoting proactive hazard identification and safety awareness campaigns has significantly reduced incidents and fostered a positive safety culture within the organization.

Caufield embodies Jacobs’ BeyondZero culture of caring and safety excellence, and her commitment to health, safety, and environmental stewardship has been a driving force behind her success.

Modifying communication is a skill that she has mastered.

“It could be senior-level CEO groups, safety talks out in the field, or discussing technical knowledge with engineers; it’s important to be able to tailor that communication and know how to speak to different groups,” Caufield says.

Caufield is also keen to encourage more female involvement.

She says, “A lot of young women just didn’t see it as a viable career path or even know it existed, but Jacobs, in my experience, has been exceptional. I work with strong female leaders, and I have young women I work with under me, but I always want to see more.”

Recognized at the national level, Caufield was entrusted with reorganizing the Canadian HSE team, leading the project portfolio across the country.

Young is a health and safety leader with over 30 years of experience in both public and private sectors.

Under the Occupational Health and Safety Act, WSPS’ mandate is to serve manufacturing, service and retail, and agriculture sectors, around 174,000 businesses, and 4.5 million workers in Ontario.

“There’s a really big demand for workplace violence and harassment, psychological safety expertise within workplaces,” says Young. “Another area in demand is materials handling, and we have a lot of warehousing and distribution centres in Ontario, and everything is being delivered to workplaces. It’s materials within tight quarters, forklifts, and transport trucks coming in, and then pedestrian safety, all in the same tight spaces.”

Previously, Young held the role of assistant deputy minister, employment and training division, with the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development, providing strategic leadership to the transformation of employment services in Ontario.

Over the last 12 months, Beauchemin has taken on a senior role at the company, which now employs over 73,900 people.

She has influenced organizational and cultural change within the Canadian region and global team of WSP, developing programs as the firm completes around 50,000 projects a year domestically.

“I have always said that safety is not a priority; it’s a fundamental commitment,” Beauchemin says. “It’s not something that today is a priority and tomorrow is not.

“I also have always been humble enough to tell people that I don't have all the answers, but we’ll work together to find the best solution we can.”

Overseeing safety management plans for four mining sites, Hruby focuses on reducing incidents, fostering collaboration, unifying processes across multiple sites, and promoting a culture of continuous learning and engagement.

Each mine has its own general manager, which adds a level of complexity for Hruby.

“You’re talking about four completely different personalities who want different things for their sites,” she says. “I can’t decide if I want to implement a whole new safety program. My approach is different with each of them in trying to get that traction.”

Adopting a forward-looking approach is a strategy that helps Hruby to stand out in the industry.

She says, “I am not big on being reactive; I want to be proactive in everything we do. It’s always looking ahead a month or two months: what kind of issues are we going to face, putting processes in place, and spending the money where we need to get to where we want to be down the road.”

A long-standing advocate of health promotion and disease prevention in occupational settings, Dorman also holds a doctorate in physiology/pharmacology and works directly with industries and the public sector to mitigate risks.

One initiative co-launched under her leadership is CROSH’s innovative multidisciplinary mobile research lab, which travels to workplaces throughout Northern Ontario, providing, among other services, group training and private health consultations for workers.

Dorman has led the introduction of a heat stress toolkit in collaboration with the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW), which has three themes.

“We wanted to update the educational materials because people are mostly aware that you can have a heat stroke event, but many are unaware that heat stress is an occupational illness,” she says. “It’s not just about not dying at work today; it’s about not getting kidney disease and dying early 15 years from now.”

The second part was focused on wearable tech.

Dorman says, “It is around trying to give health and safety specialists in the workplace information to understand what are going to be the benefits of using them, what they should be looking for in a tool, and what they should be avoiding. And the third promoted using the humidex tool and giving a more hands-on assessment of what your heat environment is for that day in your workplace.”

Welcoming the next stage of safety, Dorman is working with Equivital to pilot wearable technology for heat stress management.

The wearable, which would go on the worker’s upper arm, will estimate core body temperature and heart rate, applying American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) standards.

“It will directly alert the worker if their heart rate gets above 80 percent of their maximal heart rate for five minutes, and if their estimated core temperature gets above 38 degrees, then the worker will ideally listen to that alert and rest,” Dorman says.

The wearable will also tell workers when they’ve been resting long enough that their heart rate and core temperature have gone back down, so now they can return to work.

Dorman says, “This will hopefully be ideal in the sense of productivity, too. If you can keep the workers’ temperature down, then they can keep working. For mine workers this past fall, it was so hot, and they were faint; it wasn’t good. The people I hear from a lot are teachers, but they’re not in ventilated buildings, and they’re standing all day. Climate change is affecting everybody.

“With heat exhaustion, not only are you down for days after, but often people can't tolerate the heat again for months and sometimes years later. You’ve got a talented worker, and they have a heat stroke event. Not only is that bad for their health, but they may be out of a job because they may not be able to tolerate the heat again.”

Also innovating is Hruby, as she builds on some substantial headway already achieved. Of the four mine sites she oversees, only one incurred an LTI in the past year.

“When we talk about injury reduction, we’re not where we want to be as far as stats per se, but for LTI we’re doing phenomenally compared to our mining industry peers, based on the Mining Association of BC stats,” she says. “But we have a long mountain to still climb in alignment and really reducing injuries.”

To do so, Hruby is refining practices to ensure injuries are a learning process. After any incidents, an investigation occurs with supervisors and coordinators.

She says, “We go into the incident itself, corrective actions, root causes, and lessons learned, and that’s where I play a part. I go into the incident review online and make sure we are hitting all the boxes appropriately and haven't missed anything.”

The next stage is cross-questioning the workers involved, supervisors, and the safety team.

“From there, I’m part of producing the lessons learned document, and we have weekly calls on incident reviews with upper-level management, at which I speak on the incidents and what we're going to do to help correct them going forward,” Hruby says.

Hruby is implementing the safety philosophy program, human and organizational performance (HOP), which focuses on understanding the context and conditions of work and recognizing the complex interactions between people and systems.

She says, “We’re trying to ensure that we’re looking ahead rather than being reactive. We’re implementing a lot of changes as a team, combined collectively, that are only going to enhance things moving forward.”

WSP has more than 1,200 employees in Canada, with over 500 project managers, so Beauchemin has operational input on a large scale. Over the last 12 months, she has led on excavation.

“A big task force was created because we use the most drillers in Canada, and we needed to make sure that our excavation procedures were really clear,” she says.

Beauchemin has also played a key role in the firm’s safety culture consistency. Part of that saw her help her new superior understand the status quo.

She says, “My job was to make sure that he was coming in and continuing what we have started, not reinventing the wheel. So that he could deploy his ideas but also keep moving forward because the company has been through several acquisitions, so to keep that motivation, we couldn’t restart all of our plans again.”

Another key initiative that’s been implemented is ensuring safety advisors are placed in the appropriate roles throughout the vast firm. Before, advisors were assigned to projects without much consideration.

“I didn’t have the services to interview them and make sure I was providing the right person for that team,” says Beauchemin. “Operations were doing the selection, and we were disconnected from them, but now we have a branch that really supports the needs of resources on project sites.”

WSP is no longer a pure engineering firm and is involved in a bigger variety of projects, even acting as the prime contractor on some.

Beauchemin says, “For the thousands of smaller projects, all of my advisors are supporting young supervisors that need more love because they wear several hats and are less experienced. Now each branch of our company is well supported by us.”

Bringing the right attitude into the workplace is something Malaryk prioritizes. She explains how often workers can lose focus in continually following guidelines in what they may deem as something small, such as wearing goggles.

“It’s trying to keep high energy around the day-to-day so that people are excited about safety and have that excitement and are eager to be interested in keeping themselves safe,” she says.

However, while energy is part of her approach, if an incident does occur, it has a personal impact.

She says, “It’s pretty disheartening because you never want somebody to come to work and get injured; regardless if it’s just a minor cut, none of us prepare for that. But the next day you come in is a brand new day; the past has happened, and it’s a restart.”

Malaryk also keeps a momentum to her efforts by keeping workers engaged with a full safety calendar.

“In May, we have construction safety week; from June to August, we hold Summer Slam when people are planning vacations, so we have different housekeeping challenges,” she says. “Then from October to December, we do Finish Strong, which is geared toward looking at past incidents through some of that predictive AI data that we have and what our Life-Saving Actions (LSA) assessments are showing.”

Over the last 12 months, Malaryk’s team at Kiewit released a project safety handbook providing a wealth of information for all on site, along with QR codes for further education.

She says. “It fits into the vest or into the pocket, and basically all our safety expectations and safety programs are at somebody's fingertips. If I’m working on an operation and I’m spotting for heavy equipment, the handbook shows what we expect, the hand signals, when a spotter is required, and shows a ground disturbance procedure. It has helped us get clarity in the field on what the expectations are.

“It also gives them a means to troubleshoot questions immediately, instead of going back to their supervisors or having to call somebody, wait, and potentially keep themselves exposed to a hazard.”

Caufield provides technical guidance to engineers for their building and infrastructure projects and audits the health and safety program at Jacobs. Part of her role has been to include elements that are beyond the obvious safety dangers.

“We’re really incorporating ESG, so environmental sustainability and governance, right into our health and safety program, and we’re very much expanding our health and safety program to include mental health and psychosocial safety.”

Caufield’s high level of technical expertise is invaluable when an accident occurs. She assumes the role of lead investigator and manages the team with precision.

She says, “First, we make sure everyone is in a safe place, but then we start collecting evidence; I freeze the scene and start collecting witness statements, getting as much information and photographs as possible. Then I do a root cause analysis, which I’m trained to do.”

It’s uncommon that there is one factor behind an incident; it comes down to multiple factors.

“We look at how it happened but also at the health and safety management level,” Caufield says. “Where did it go wrong in the policy, procedure, and management plan? And then I offer corrective actions based on that, where we can fix it at the field level but also fix it at the program level, so we don't see it repeat.”

This is all then reviewed six months later.

Caufield says, “We check those corrective actions to make sure they have been effective.”

In her leadership role at WSPS, Young has seen an increase in demand for expertise in violence and harassment and psychological safety expertise within workplaces to protect their workers.

“Workplace violence and harassment have become real hazards, particularly post-pandemic, and especially for workers who interact with the public; it’s becoming more and more challenging,” she says.

WSPS has published a white paper on the hazards related to the handling of electric vehicle batteries.

Young says, “We’re forging ahead converting a lot of our plants from gas-powered to electric, and we haven’t addressed all the hazards in the supply chain of the battery. It’s one thing to put it in the car safely, but down the chain for mechanics, the auto body shops, and then the disposal sites to be handling the batteries, that’s one area that’s really emerged.”

Despite serving over 4.5 million, WSPS only employs 250 staff in the organization, which can prove difficult.

“The challenge for us at WSPS is to raise awareness among all the businesses that we serve that we exist, we’re here to help, and we’re different from the compliance and enforcement side of the health and safety system,” Young says.

With increased immigration into Ontario, WSPS has invested in multilingual services and supports.

“We entered into memorandums of agreement with over 25 settlement agencies across the province, whereby we train the settlement agency staff in basic health and safety, so they can then train in the language that these new immigrants can understand. This acclimatizes them to what their workplace rights and responsibilities are in Ontario. That has been an incredible initiative.”

As skilled trades have become an emerging need, WSPS has visited high schools across the province that have tech shops.

Young says, “Last year, we examined over 4,500 pieces of equipment for safety precautions. We’ve trained up teachers to ensure that the surroundings for the students are safe and that they’re teaching them best practices around safety before they leave high school to head out into the workplace.”

Prior to joining Jacobs, Caufield worked for a power line utilities company, providing health and safety to high-risk occupations such as transmission, live line distribution, and heavy construction.

She says, “We did emergency response in the United States; when the hurricanes came in, we’d go and work on the power grid. The learning benefits from that were just unparalleled.”

One of those lessons was how to deal with working in male-dominated fields.

“Often, I’d be the only woman in a group of 80–100 people,” she says.

This brought its own set of issues for Caufield.

She says, “My experience with the field crews was good, but there were a lot of challenges. With PPE, they would just hand you a pair of small men's clothes, but it fits wrong in all the places. With washrooms, you’d be on a job site, and there’s only one male porta-potty, that’s many kilometres down the road, and you're just like, ‘Okay, we'll share this.’

“Unfortunately, there were also some challenges with leadership and their confidence in your ability to lead a team of men. Sometimes they weren’t sure how the field crew would respond to me as a woman, and I ran into that a few times.”

There are still instances when Hruby is the only female in the room. When advising female managers and coordinators, she focuses on the importance of education and knowledge of the industry.

She says, “You have to know your stuff and get boots on the ground, throw some coveralls on, and get in there. Don’t be afraid to say what you don’t know; don’t come up with a story on why something might be if you don’t know yourself, because it’s gaining the respect in the room. If you can gain the respect in the room, then you’ll go places.

“It’s not about being afraid to speak up but being educated and listening with intent. When you’re talking to somebody, and you’re always trying to come up with an answer, versus truly understanding what they have to say, you’re going to lose a lot of respect from people. When your workers don’t respect you, you’ve already lost the game. You can’t come back from that.”

Young believes that more women need to be encouraged into the OHS sector.

She says, “There are way more women in health and safety now than there ever were before, but we need to keep that momentum. There are a lot of us who feel the obligation to give back to other women leaders and build them up within our system. There is a real movement and a momentum that’s happening in that regard. I have been very blessed to have some incredible female mentors along my path.”

Women in Kiewit is an initiative that Malaryk is heavily involved in and is able to bring her first-hand experience.

“It definitely has improved, but I spent a lot of time working in Fort McMurray, and there were times when I was the only woman on a project for months at a time,” she says.

There is a committee that develops the existing team as part of Women in Kiewit and also another committee that does outreach to bring people into the industry.

Malaryk says, “It’s about being able to let everybody know that as a woman, I’ve been in your shoes; I potentially could have had the same experiences. I want them to know that we’re here for one another, and this is what we tolerate and this is what we don’t.”

Canadian Occupational Safety invited OHS professionals from across the country to nominate exceptional female leaders for the fifth annual Top Women in Safety list. Nominees had to be working in a role that related to, interacted with, or in some way influenced the health and safety sector. They must also have demonstrated a commitment to their profession.

Nominators were asked to describe the nominee’s standout professional achievements over the past 12 months, the initiatives and innovations, and contributions to the OHS industry.

To narrow down the list to the final 70 Top Women in Safety, the COS team reviewed all nominations, examining how each individual had made a meaningful contribution to the industry.