Occupational exposure series: They were young, they never thought they were going to die, says former UNIFOR Local president

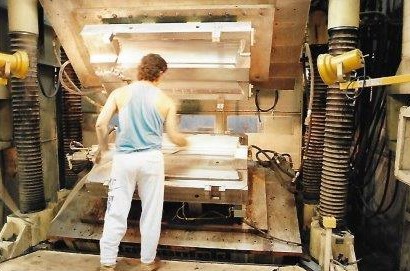

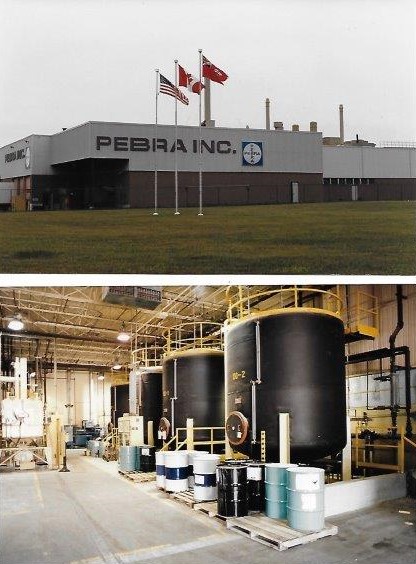

“I was the one that first noticed that something was wrong with our plant,” says Rose Wickman. The plant in question is the former Pebra Plastics plant in Peterborough, Ontario.

German company Pebra owned and operated the plant from 1986 until 1996 when it went bankrupt. It switched hands a few times over the next couple of years.

The plant was bought by Ventra, operated by them until 2001 and though it's still called Ventra Plastics, it is now owned by the Flex-N-Gate Group of Companies.

Wickman served as president of UNIFOR Local 1987 for 28 years before retiring in 2017, but she remains heavily involved in the fight to bring justice to workers from the “Pebra era.”

Lost in the shuffle

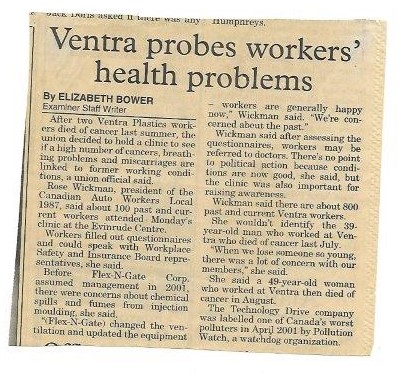

During the years it was operated by Pebra, Wickman explains that she was concerned with the large number of young workers dying of various illnesses.

She reached out to Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) – her union at the time – and the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers Inc. (OHCOW) but her concerns “got lost in the shuffle” until 2004.

That year, workers from the Ventra/Pebra plant did an OHCOW clinic with the workers from the GE plant in Peterborough, workers came forward with their issues and this renewed interest in the Pebra workers.

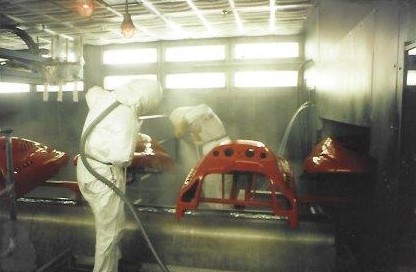

During their time at the plant, workers were aware of the troubling working conditions: “We were the number one plant for our work refusals. The Ministry [of Labour] said that they had two filing cabinets full of refusals because we were noticing people getting headaches, people were getting dizzy, were getting nosebleeds,” says Wickman. “They were sick to their stomach.”

Wickman explains that in addition, female workers were having issues with abnormal menstruation and even miscarriages.

She says that every night, workers would have to go to local hospitals with their health issues – it got to a point, she says, where hospitals told the workers to stop coming.

Families affected

Though working conditions have improved immensely under new leadership, Wickman is still fighting to get justice for workers from the Pebra era.

“Even though I’m retired, I still stay involved because the workers [have] become like family, and to lose so many coworkers and friends…it’s hard.”

Because the plant was such a large employer in the area, whole families have been affected.

“I personally suffered, I lost a brother who was a worker there for 29 years,” she says.

Wickman says that she knows a father who had two different types of cancer, and eventually had a heart attack. His son was affected neurologically, from what is believed to be exposure to chemicals at the plant. A mother and daughter who worked at the plant both died of massive heart attacks.

“It’s just astronomical the amount of deaths we’re having, and it just seems like every week there’s another one.”

Speaking of her brother, Wickman says that he was diagnosed with his cancers in 2014. He started his claim and his argument but sadly passed away in 2018.

Wickman and her family are still in the process of fighting his claim because it has been denied. Many of the claims, she says, have been denied by the WSIB.

And Wickman says that despite a report published by OHCOW in 2020 of the exposure profile of the Pebra Plastics plant (1986 – 1996), claims are still being denied.

She says that the WSIB points to lifestyle factors such as obesity or smoking as the cause for the illnesses rather than chemical exposure.

However, says Wickman, “the people that they are calling obese weren’t obese. And I know from experience. My brother was very physically fit, but after he got his cancer the medication absolutely made him obese – but that was just part of the process.”

Toxic exposures

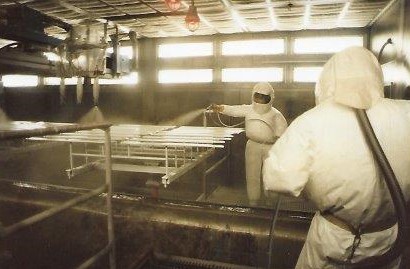

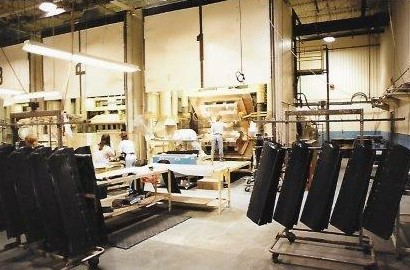

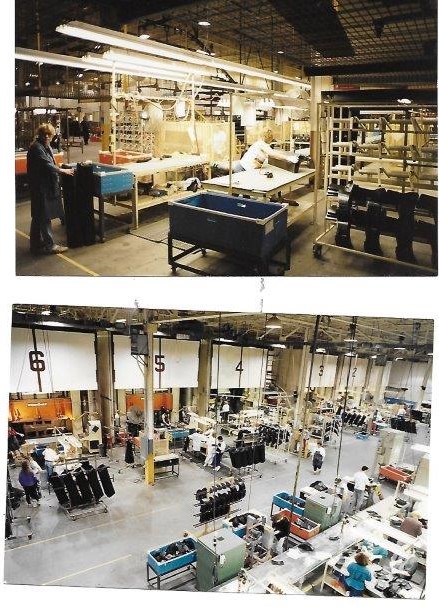

Workers at the plant were exposed to a number of toxic substances. The 2020 report confirmed that there were a large number of carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC) used at the plant.

The OHCOW report lists, among many others: benzene, silica, resin dust containing isocyanate residues, asbestos, vinyl chloride, phthalates, acrylonitrile, styrene, 1,3 butadiene, cadmium, lead, trichloroethylene, toluene, methyl ethyl ketone, xylene, epichlorohydrin, Bisphenol‐A, welding fumes, metal working fluids, and isocyanates.

And workers have developed an array of cancers such as lung cancer, breast cancer and kidney cancer. There are also respiratory issues such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The building was an open plant, and so all departments were in contact with harmful chemicals.

“When we first started working […] they told us that there was nothing harmful in there that would hurt us. That is was no different than the green slime that kids play with.”

But this was false, says Wickman, and in fact a watchdog back in the day found that the Pebra plant was a top polluter in the area.

“Our schools and our neighbours were complaining about the smell coming from our plant.”

Efforts were made to try and shut the plant down, “and it just seemed like nothing ever happened,” she says. “And now people are paying the price with their lives.”

Wickman explains that there was also an issue with ventilation at the plant – but it was swept under the rug by management at the time.

Before an external inspection happened, she says, “the company would open every door in the plant, and every window, and air it all out to make sure that when the Ministry got there to test [the air], it was all clear.”

30 years later

Wickman says she hears of workers getting ill so often: “About once a month we’re hearing that another worker got cancer, or another worker is dead.”

Wickman says that of the 125 people who made compensation claims, over 75 have since died. Many of whom were only in their 50s or early 60s.

As we have seen in the other parts of our series, many diseases stemming from occupational exposures have a latency period. It is typically only when workers are in their 40s, 50s or 60s that they may start developing symptoms.

“It’s just horrific the amount of things that you can’t even put your finger on because there’s so many different types of cancer they’re getting,” she says.

Says Wickman: “A lot of our workers were around 18. They were young, they never thought they were going to die. We all thought we were invincible. That it’s not going to affect us, it just affects other people. And now here we are 30 years later, we notice all these people dying for different reasons – and it’s scary.”

This is the fourth part of our new series on occupational exposures. Over the next few weeks, COS will be shining a spotlight on the issue and speaking with occupational disease advocates about the dangers of workplace exposures.

Here are the first (miners exposed to aluminium dust), second (exposures at GE plant in Peterborough) and third (exposures at Neelon Casting) parts of the series.